INTRODUCTION

The introduction of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) has significantly influenced vaping status, particularly among adults of reproductive age1. Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), a predominant form of ENDS, have seen a rise in use during the perinatal period, with reported rates approximating those of traditional cigarettes2,3. The prevalence of e-cigarette use among women in Greece stands at 17%, exceeding the European average of 14%. This shift towards ENDS, including newer heating, non-burning tobacco products with a use rate of 9% in Greece, higher than the European context, reflects changing patterns in nicotine consumption4.

Some people perceive e-cigarettes, which generate an inhalable vapor by heating a liquid solution, as a safer alternative to conventional smoking5. Young adults have seen a surge in popularity due to this perception and aggressive marketing6. With over 500 brands and 8000 flavors available, e-cigarettes have become a staple of nicotine use in modern society7.

Despite the popularity of e-cigarettes, users often encounter potentially harmful substances like formaldehyde and metals, sometimes at levels comparable to or exceeding those in traditional cigarettes. E-cigarettes are capable of delivering nicotine levels potentially greater than those of traditional cigarettes, which contain about 10–15 mg of nicotine each. The market offers e-liquids with nicotine concentrations ranging from 0 to 36 mg/mL8. Moreover, a recent study revealed that despite being marketed as lower risk alternatives to traditional cigarettes, heated tobacco products emit high concentrations of particles, which vary based on the smoking method, the flavor selected, and the operational settings9.

In the United States, more than 10% of pregnant women smoke during their pregnancy, and the rate of maternal vaping is estimated to be similar10. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is a well-established risk factor for a range of adverse perinatal outcomes, including prematurity, low birth weight, congenital heart defects, cognitive deficits, intrauterine growth restriction, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)11-13. Efficient nicotine delivery via e-cigarettes is of particular concern during pregnancy, as nicotine readily crosses the placenta. This can lead to fetal nicotine concentrations exceeding maternal levels, which may impact oxygen delivery to fetal tissues14. A prior attempt at a systematic review and meta-analysis (with searches performed through 2018) found no articles that reported pregnancy outcomes following ENDS use15. In 2021, according to a systematic review which examined the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes following the use of ENDS during pregnancy, ENDS use is associated with increased risks for some adverse outcomes, such as small for gestational age (SGA), but the evidence is mixed and insufficient due to repeated datasets, insufficient data on timing and type of ENDS used, and limited sample sizes. Dual use of ENDS and conventional cigarettes (CCs) showed heightened risks, similar to or greater than CC use alone. The review concludes that current data do not support recommending ENDS as a safer alternative to CCs during pregnancy and emphasizes the need for pregnant women to quit all tobacco products16.

Despite the high risks, comprehensive data on e-cigarette use during pregnancy is scarce, highlighting the urgent need for research in this area.

While some view them as a less harmful option, the reality of their impact, especially on fetal development and pregnancy outcomes, remains inadequately explored. Given the ever-changing landscape of nicotine delivery methods and the critical gaps in our understanding of their safety, this systematic review aims to scrutinize the available literature on ENDS use during pregnancy. It seeks to assess their potential effects on fetal health and pregnancy outcomes, contributing to the ongoing discourse on the advisability of their use during pregnancy.

METHODS

We conducted a comprehensive literature search using the databases: Scopus, Medline (PubMed) and Web of Science to conduct a systematic review on the impact of ENDS on fetal health and pregnancy outcomes. The search aimed to gather scholarly articles, focusing on studies that examine the effects of ENDS on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. The search was restricted to articles in English to ensure comprehensibility and accuracy in the analysis.

Search strategy

The keywords used for the search were a combination of terms related to pregnancy and ENDS: [pregnancy OR pregnancy complications OR pregnancy outcome OR newborn OR neonate OR birth] AND [electronic cigarettes OR heated tobacco products OR vaping OR e-cigarettes OR vape OR IQOS OR ENDS OR electronic nicotine delivery systems]. We selected these keywords to encompass a wide range of pertinent research areas, such as the application of diverse ENDS and their possible effects on pregnancy and neonatal health (Supplementary file). We have also registered the review protocol on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with ID number CRD42024559079.

Grey literature

We also searched the grey literature to identify studies not published in peer-reviewed journals. Sources included clinical trial registries, conference proceedings, and government reports.

PICO framework

To guide the systematic review, we formulated a PICO question to address the impact of ENDS on pregnancy outcomes. The PICO framework is defined as follows:

Patient/Problem (P): Pregnant women who use electronic ENDS

Intervention (I): Use of ENDS during pregnancy

Comparison (C): Non-use of ENDS or use of conventional cigarettes (CCs)

Outcome (O): Adverse perinatal outcomes such as SGA infants, PB, and LBW

PICO question

The question was: ‘In pregnant women (P), how does the use of electronic nicotine delivery systems (I) compared to non-use or use of CCs affect the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes such as SGA infants, PB, and LBW (O)?’.

This framework guided the selection of studies and the analysis of data to ensure a focused and comprehensive evaluation of the effects of ENDS use during pregnancy.

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria for the articles were: 1) Full-text articles to ensure accessibility for analysis and review, 2) Studies published in English to maintain consistency in language for analysis, and 3) Studies specifically involving pregnant women to directly address the review’s focus on pregnancy outcomes and fetal health in the context of ENDS use.

Quality assessment and bias evaluation

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies. This tool evaluates studies based on three broad perspectives: selection of the study groups, comparability of the groups, and ascertainment of the outcome. Each study was scored out of a possible 9 points, with higher scores indicating higher quality.

For randomized studies, the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was utilized. This tool assesses bias across several domains, including selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other potential sources of bias.

The quality assessment process involved the following biases:

Selection: evaluating the method of participant selection;

Performance: assessing the risk of bias due to differences in care provided, apart from the intervention being studied;

Detection: examining the methods used to measure outcomes;

Attrition: considering the completeness of outcome data; and

Reporting: checking for selective outcome reporting.

Each study was independently assessed by two reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

Reporting guidelines

This study follows the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines to ensure comprehensive and transparent reporting of observational studies. A completed STROBE checklist is included in the Supplementary file.

Data extraction

Two independent researchers performed the search and data extraction.

The following types of information were extracted for each study:

Author(s) and year of publication;

Location;

Methodology: sample, data source, study design, details on how participants were grouped based on their smoking and vaping behavior, such as non-smokers, CC users, and electronic cigarette users, and data collection period;

Variables measured: exposures, outcomes;

Results: main findings and statistically significant differences; and

Conclusions: main conclusions regarding the impact of ENDS use on pregnancy outcomes.

GRADE evaluation

The quality of evidence for each outcome was assessed using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach. This method evaluates the certainty of evidence based on factors such as study limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias.

Statistical methods

Effect size synthesis: the primary measure was odds ratio (OR), as all studies reported ORs.

Meta-analysis: random-effects models were used to account for variability between studies17. Due to the limited number of studies, the DerSimonian and Laird method with a Hartung-Knapp adjustment was employed for a more robust estimation. This method provides more accurate confidence intervals when dealing with small sample sizes and potential heterogeneity.

Evaluation of heterogeneity: assessed using the I² statistic. An I² >50% is considered indicative of substantial heterogeneity18.

Publication bias: assessed using both graphical and statistical methods. Funnel plots were generated to visually inspect asymmetry, and both Egger’s regression test and Begg’s test were performed to statistically test for publication bias. Non-significant results in these tests indicate the absence of small-study effects.

Software: All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA 15.0.

RESULTS

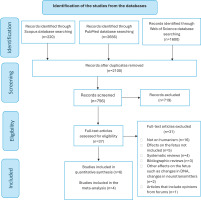

The initial search yielded a significant number of articles: 220 from Scopus, 2656 from PubMed and 1600 from Web of Science. Application of the first two selection criteria refined the results to 145 articles in Scopus and 1276 in PubMed and Web of Science. Further screening for articles that specifically involved studies on pregnant women (third criterion) narrowed the results down to 37 articles. Only six of these met all the specified criteria and were considered relevant for the systematic review.

We identified six articles that assessed adverse pregnancy outcomes in women who used ENDS during pregnancy. Table 1 summarizes these articles and Figure 1 illustrates the flow diagram detailing the methodological approach, including the search strategy and the screening process for the selection of the articles.

Table 1

Studies included in the systematic review

| Authors Year Country | Sample | Methodology | Results and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kim and Oancea19 2020 USA Included in meta-analysis for SGA, PB and LBW | Data collected between 2016 and 2018. Sample: 55251 pregnant women Database: PRAMS Based on any use during the last 3 months of pregnancy they were divided into: The dual use group (ENDS and CC) was excluded from the analyses (n=395) | Adverse outcomes included infants who were SGA, LBW, and were PB. The association between EC use and adverse birth outcomes was evaluated by population-weighted logistic regression analyses. Female smokers were assigned to groups based on 7 variables: race/ethnicity, age, education level, 1st trimester smoking, 2nd trimester smoking, family income, and prenatal care. | Among participants, 1% of women reported EC use during the third trimester, 60% of whom reported EC use exclusively. Infants of EC users were significantly more likely to be SGA (OR=1.76; 95% CI: 1.04–2.96), LBW (OR=1.53; 95% CI: 1.06–2.22) or be born preterm (OR=1.86; 95% CI: 1.11–3.12) compared to non-smokers. However, the odds of neonates of EC users being SGA (OR=0.67; 95% CI: 0.30–1.47), LBW (OR=0.71; 95% CI: 0.37–1.37) or preterm delivery (OR=1.06; 95% CI: 0.4–0.4) were not significantly lower than those of CC smokers. The use of EC continues to be an independent risk factor for neonatal complications and does not represent a safer alternative to CC smoking during pregnancy. |

| Wang et al.20 2021 USA Included in meta-analysis for SGA and PB | Database: PRAMS Data collected between 2016 and 2018. Sample: Pregnant women who gave birth to a live infant and had complete data on CC and ENDS use before and during pregnancy (n=99201) The sample was categorized based on CC and ENDS use during the last 3 months of pregnancy. Non-smokers (n=90198; 92.0%) ENDS use only:

CC use only:

L-CC & O-ENDS (n=230; 0.2%) L-CC & F-ENDS (n=163; 0.1%) H-CC & O-ENDS (n=212; 0.2%) H-CC & F-ENDS (n=118; 0.1%) | Perinatal outcomes: SGA, PB Two models were applied. Both were adjusted for maternal age, education level, race/ethnicity, marital status, prior history of preterm birth, multiparity, prenatal care, pre-pregnancy BMI, pre-pregnancy alcohol consumption, and the year of birth. Model B also adjusted for CC and/or ENDS use in the 3 months before pregnancy, while A did not. | While dual users who smoked heavily and vaped occasionally had the highest adjusted OR for SGA (AOR=3.4; 95% CI: 2.0–5.7), all dual users were, on average, approximately twice as likely to have SGA than non-smoking women. While the risks of preterm delivery were higher among light smokers (AOR=1.3; 95% CI: 1.1–1.5) and only heavy smokers (AOR=1.5; 95% CI: 1.2–1.8) than non-users, the adjusted odds of preterm delivery for dual users were not appreciably higher than those of non-users. Therefore, relative to non-smokers, engaging in both smoking and vaping during pregnancy seems to elevate the risk of SGA, while the heightened risk of PB is mainly associated with smoking exclusively. Higher levels of exposure tend to pose more risks. |

| Cardenas et al.21 2019 USA Included in meta-analysis for SGA | Sample: Pregnant women aged ≥18 years recruited from an antenatal clinic serving low-risk pregnant women (i.e. those with no underlying medical conditions or comorbidities and no antenatal complications) (enrolled, n=248; in pregnancy outcome analysis, n=232). Current usage (each previous month):

Current ENDS use (yes) by gestational weeks at enrollment: <20 weeks (n=12; 14.3%), ≥20 weeks (n=11; 6.8%), missing data (n=1; 50%). | Perinatal outcome: SGA The study utilized questionnaire data along with biomarkers (salivary cotinine, exhaled carbon monoxide, and hair nicotine levels). The researchers analyzed the relationship between birth weight and the risk of being SGA in multivariable linear and log-binomial regression techniques on data from 232 participants. Those who did not disclose their smoking status were excluded from the analysis. | Among pregnant women, 6.8% (95% CI: 4.4–10.2) reported using ENDS, with 75% of these also smoking CC concurrently. According to self-reported data, the RR of SGA infants for ENDS users was nearly twice that of non-users (RR=1.9; 95% CI: 0.6–5.5), and over three times higher for those exclusively using ENDS compared to non-users (RR=3.1; 95% CI: 0.8–11.7). When excluding smokers who withheld their smoking status, the risk for SGA among exclusive ENDS users rose to five times that of non-users (RR=5.1; 95% CI: 1.1–22.2) and nearly four times for all ENDS users (RR=3.8; 95% CI: 1.3–11.2). After adjusting for potential misclassification from self-reported data, the RR for ENDS users ranged from 6.5 to 8.5 times greater than for non-exposed individuals. These findings indicate a significant association between ENDS use and an elevated SGA risk. |

| Clemens et al.22 2019 USA | Sample: Pregnant women (≥18 years) recruited from prenatal clinic serving low risk pregnant women who gave birth to an infant, provided complete data for the study and provided hair samples (n=76). Current (any use within the previous month) CC and/or ENDS By self-report: Self-report confirmed by biomarkers (SR + B): ENDS user excluded (n=1) The mean gestational age for the sample was not reported. | Perinatal outcome: SGA ENDS use is defined as any use of electronic vapor products in the past month. Hair samples were collected from pregnant women involved in a prospective cohort study, including those who used both ENDS and CC (dual users), those who only smoked, and non-smokers. These samples were analyzed to measure levels of nicotine, cotinine, and TSNA. Using both these biomarkers of exposure and self-reported data on smoking and ENDS use, log-binomial regression models were applied to calculate the RR for SGA outcomes in their offspring. | Nicotine concentrations for pregnant ENDS and CC users were not significantly different from those for female smokers (11.0 and 10.6 ng/mg hair, respectively, p=0.58). Similarly, cotinine and TSNA levels for pregnant ENDS and CC users were not lower than those for female smokers. The RR for SGA was similar for ENDS and CC users and smokers compared to non-smokers (RR=3.5; 95% CI: 0.8–14.8) and (RR=3.3; 95% CI: 0.9–11.6), respectively. Using self-reports confirmed by hair nicotine, the RR values for dual ENDS users and female smokers were 8.3 (95% CI: 1.0–69.1) and 7.3 (95% CI: 1.0–59, 0), respectively. ENDS and CC users compared to female smokers during pregnancy. The risk of SGA outcomes for the offspring of pregnant women who were dual users was comparable to that of offspring from women who smoked cigarettes alone. |

| Regan and Pereira23 2021 USA Included in meta-analysis for SGA, PB and LBW | Database: PRAMS. Data collection period: 2016 to 2018. Sample: women who recently gave birth to a single child weighing at least 400 g, who reported smoking combustible cigarettes in the two years before pregnancy, and whose records included complete details on exposure, outcome, and covariates (n=16022). The participants were divided into four groups:

| Perinatal outcome was studied: PB, SGA and LBW. Women were required to self-report on their use of CC and EC, specifying whether they had used these products during the three months before pregnancy and in the final three months of pregnancy. Additionally, those who continued to smoke CC while pregnant were asked to indicate their daily cigarette consumption, choosing from the categories: <1, 1–5, 6–10, 11–20, or ≥21 . The responses from these questionnaires were then correlated with data from the birth certificates, which included sociodemographic details as well as health information for both the mothers and their newborns. | Among the study participants, 8.9% (95% CI: 8.4–9.5) experienced preterm births, 13.7% (95% CI: 12.9–14.6) had infants classified as SGA, and 8.4% (95% CI: 8.0–8.9) had LBW infants. Women who had stopped smoking CCs and avoided EC (ex-smokers) showed a lower occurrence of PB (APR=0.70; 95% CI: 0.61–0.81), SGA (APR=0.46; 95% CI: 0.40–0.53), and LBW (APR=0.53; 95% CI: 0.47–0.60) compared to current smokers. Although adverse birth outcomes were less common among sole EC users than current smokers, there was no significant reduction in the prevalence of PB (APR=0.85; 95% CI: 0.55–1.31), SGA (APR=0.56; 95% CI: 0.29–1.08), or LBW (APR=0.81; 95% CI: 0.54–1.21). When compared to ex-smokers, both EC-only users and dual users exhibited similar rates of PB (APR=1.21; 0.78, 1.87, and 1.26; 95% CI: 0.91–1.73, respectively). However, EC-only users had a higher incidence of LBW (APR=1.52; 95% CI: 1.01–2.29) compared to ex-smokers, and dual users showed higher incidences of both LBW (APR=2.11; 95% CI: 1.6–2.77) and SGA (APR=2.60; 95% CI: 2.00–3.38). The rate of SGA births among EC users was similar to that of ex-smokers (APR=1.22; 95% CI: 0.63–2.34), and there were no notable differences in adverse birth outcomes between dual users and current smokers. Therefore, this study indicates that using e-cigarettes does not assist in reducing CC use among pregnant women or provide any apparent benefits to fetal health, supporting the recommendation for complete abstinence from both CC and EC during pregnancy. |

| Ashford et al.24 2021 USA | Sample: 279 pregnant women in the 1st or 2nd trimester of pregnancy from January 2016 to March 2020. A total of 4688 women were approached, of whom 391 met eligibility criteria based on maternal age (18–44 years), pregnancy (first or second trimester), current tobacco use [CC, ENDS, or both (dual users)] and the ability to read or write in English. Of these, 278 gave informed consent to participate in the study; 59 participants who completed only the 1st trimester surveys were excluded, as was 1 participant who remained a non-smoker throughout pregnancy. Thus, the final analysis sample was n=218. The women were categorized into groups according to whether they changed their smoking status: Switching behaviors were complex and not easily grouped. For example, participants who reported only conventional use at enrollment tended to switch to dual use in the second trimester (n=15), but a third then returned to conventional use in the third trimester (n=5). Two contract enrollment-only users switched to ENDS-only use in a later quarter. Similarly, recurrent changes in product use were observed in participants who reported dual use at enrollment but then switched to conventional-only (n=27) or ENDS-only (n=5) in a later quarter, while three returned to dual use. ENDS-only users at enrollment mostly switched to dual-use (n=6) and less frequently to conventional (n=1), but one subject switched from ENDS-only at enrollment to dual-use to conventional-only during pregnancy. | Women’s use of tobacco products was measured in each trimester of pregnancy using self-report. Birth outcomes were obtained from the electronic medical record of the delivery hospital and were defined as:

| There were no differences between groups in gestational weeks at delivery, respiratory distress in the first 24 hours of life, or transfer to the NICU (p>0.05). However, newborns of participants who stopped smoking were observed to weigh 304 g more than newborns whose mothers did not change smoking status (mean difference=304, p=0.0439). Also, the neonates of pregnant women who changed their smoking status were on average heavier than the neonates of those who did not change (mean difference=182.79, p=0.4462), but this finding did not meet the criteria for statistical significance. |

[i] PRAMS: a routine, continuous surveillance system that collects information on preconception, prenatal, and postpartum health, implemented by states and coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. EC: e-cigarette. CC: conventional cigarette. BMI: body mass index. ENDS: electronic nicotine delivery systems. PB: preterm birth. SGA: small-for-gestational age. RR: relative risk. TSNA: tobacco-specific nitrosamine. APR: adjusted prevalence ratio. NICU: neonatal intensive care unit. LBW: low birth weight.

Figure 1

Flow diagram detailing the methodological approach, including the search strategy and the screening process

Kim and Oancea19 analyzed perinatal outcomes [SGA, low birth weight (LBW), and preterm birth (PB)] in users of ENDS, CCs, or neither, excluding dual users. Compared to non-tobacco users, ENDS-only users had significantly higher odds for SGA, LBW, and PB, but these were not significantly different from CC-only users.

Wang et al.20 examined PB and SGA in ENDS-only, CC-only, and dual users, categorized by frequency. Dual users had double the SGA incidence compared to non-users, but ENDS-only users showed no significant increase in SGA odds. Neither ENDS-only nor dual users had significantly higher PB odds compared to non-users.

Cardenas et al.21 found that ENDS-only users had a three-fold higher SGA risk compared to non-users, with risks increasing to 6.5–8.5 times when excluding those with nicotine biomarkers.

Clemens et al.22 showed that ENDS, CC, and dual users had a fourfold higher SGA risk, rising to eightfold with nicotine biomarker confirmation. High nicotine exposure alone was associated with a 7.7-fold higher SGA risk.

Reigan and Pereira23 reported that ex-smokers had the lowest PB, SGA, and LBW rates. ENDS-only users had fewer adverse outcomes than current smokers but no significant improvements. Dual users had higher LBW and SGA rates than ex-smokers and no benefits over current smokers, recommending complete abstinence during pregnancy.

Ashford et al.24 studied 391 pregnant women, categorizing 218 based on smoking behavior changes. Birth outcomes included gestational age, birth weight, respiratory distress, and NICU admission. The analysis showed no significant differences between groups in terms of gestational age at delivery, respiratory distress, or NICU admissions (p>0.05). However, infants born to mothers who ceased smoking were significantly heavier by 304 g compared to those whose mothers maintained their smoking status (mean difference=304, p=0.0439). Additionally, infants from mothers who changed their smoking status tended to be heavier than those from mothers who did not, with a mean difference of 182.79 g, although this was not statistically significant (p=0.446).

Comparison of ENDS and conventional cigarette smoking

The comparison between ENDS and CC smoking on pregnancy outcomes from several studies indicates that both nicotine delivery methods pose significant risks. Studies by Kim and Oancea19 and Clemens et al.22 found no significant differences in adverse outcomes such as SGA, LBW, and PB, between ENDS users and CC smokers, suggesting that ENDS are not a safer alternative. Similarly, Wang et al.20 and Cardenas et al.21 reported increased risks of SGA among both ENDS and CC users, with dual users showing particularly high risks. Regan and Pereira23 further supported these findings, indicating that e-cigarette-only users did not experience significant reductions in adverse outcomes compared to current smokers. Overall, the evidence underscores the recommendation for complete abstinence from all forms of nicotine during pregnancy to ensure optimal perinatal outcomes.

Meta-analysis

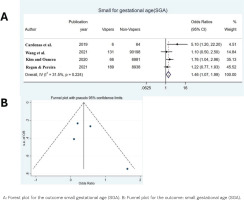

Our meta-analysis included 4 studies for the outcome SGA, 3 for the outcome PB and 2 for the outcome LBW (Table 1). The median sample size was 35636.5 (range: 4191.5–88213.5). From the meta-analysis of the results of the 4 included studies on SGA, the OR was found to be 1.46 (95% CI: 1.07–1.99, p=0.05), indicating that women who used e-cigarettes had a 1.46 times greater risk of having a baby smaller than normal for their gestational age, compared to women who did not use e-cigarettes (Figure 2A). Heterogeneity between studies was not significant (overall Q=4.38, p=0.224, I2=31.5%) so a fixed effects model was used to calculate the OR. From Figure 2B there does not seem to be any error which is confirmed according to Egger’s test [bias coefficient=1.81, standard error (SE)=1.60, p=0.375].

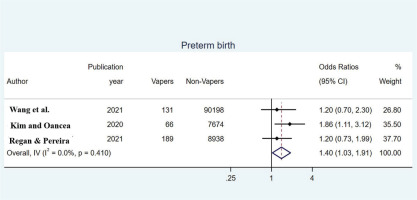

Estimates of the OR for PB from the 3 included studies are shown in Figure 3. Heterogeneity between studies (pooled Q=1.78, p=0.410, I2=0.0%) was not significant, so using a fixed-effects model estimated the overall OR equal to 1.40 (95% CI: 1.03–1.91), indicating a significantly increased risk of preterm delivery for women who used e-cigarettes compared to non-users of electronic cigarette. More specifically, those who vaped had a 1.40 times increased risk of preterm delivery compared to those who did not vape.

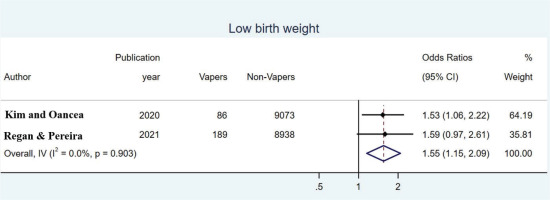

In estimating the OR for LBW, two studies were included between which heterogeneity was not significant (overall Q=0.01, p=0.903, I2=0.0%) so a fixed-effects model was used. The pooled OR was found to be 1.55 (95% CI: 1.15–2.09) indicating that babies of women who used e-cigarettes were 1.53 more likely to have LBW than babies of women who did not used them (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

The findings of this meta-analysis add to the growing body of literature regarding the risks associated with ENDS use during pregnancy. Consistent with previous reviews and meta-analyses, our results indicate that the use of ENDS during pregnancy is associated with increased risks for SGA infants, PB, and LBW16. These outcomes mirror those seen in pregnancies impacted by CC smoking, implying that ENDS may not be the safest option pregnant women often believe it to be25,26.

The increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes could be attributed to nicotine, which is a common component of both traditional cigarettes and most ENDs. Studies have demonstrated that nicotine impairs fetal brain and lung development, disrupts the architecture of developing neural circuits, and decreases placental blood flow, potentially contributing to conditions such as SGA and PB27,28. Despite the marketing of ENDS as having fewer toxicants than CCs, variations in device mechanics, usage patterns, and liquid composition can result in significant exposure to nicotine and other potentially harmful substances29.

The prevalence of ENDS use during pregnancy varies across studies. According to a US population-based study, around 5% of pregnant women use ENDS, which is consistent with the general adult prevalence. However, clinical settings and online populations have reported higher rates of use (12–14%). Similar to trends seen in non-pregnant adults, the majority of pregnant women who use ENDS are also likely to smoke CCs concurrently, indicating dual use15. Interestingly, our study found that despite the known risks, a significant proportion of pregnant women choose to use ENDS, possibly due to marketing strategies that highlight these products as less harmful alternatives to smoking. This misconception underscores the need for clearer communication regarding the risks associated with nicotine in any form during pregnancy. Public health policies and prenatal care practices should actively dissuade all forms of nicotine consumption during pregnancy, emphasizing the lack of safety data supporting ENDS use30.

The current study’s findings are particularly relevant in the context of regulatory policies. While there have been significant advancements in tobacco product regulation, including ENDS, regulatory frameworks frequently lag behind the rapidly evolving product landscape. There is a pressing need for updated and stringent regulations that reflect the latest evidence on the health risks associated with newer tobacco products, especially for vulnerable populations such as pregnant women31. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plays a crucial role in addressing public health concerns related to smoking CCs and ENDS during pregnancy by making informed regulatory decisions regarding ENDS products32.

According to the available evidence, public education initiatives and warning labels could also play a significant role in influencing perceptions about the risks associated with ENDS and their potential to mitigate harm to newborns. According to Tauras et alo.33, the use of warning labels has been successful in reducing the prevalence of CC smoking among pregnant women. A challenge for authorities may be the lack of information about the types of product features used by pregnant women and how these relate to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Before using ENDS as a harm reduction strategy, pregnant women should adhere to existing clinical guidelines and consider evidence-based cessation therapies approved for use during pregnancy34.

Furthermore, many ENDS users report difficulties understanding the nicotine content and other characteristics of the products, complicating the collection of accurate research data on these aspects35. Clear labeling on packages that distinctly specifies the nicotine amount in the product and the quantity delivered to users, particularly in comparison to CCs, would empower consumers to make well-informed choices regarding self-administration and enable them to adjust their own nicotine intake. Standardizing this information across all brands and devices would enhance consumer knowledge.

Integrating these data into public education campaigns could also enhance overall awareness of these issues and, consequently, lead to more precise clinical data concerning the characteristics of products used during pregnancy. Although less frequently reported, some studies found that pregnant women reported a lower purchase price than CCs as a reason for using ENDS, so taxation may address this concern, as taxes are an effective tool to reduce the prevalence of ENDS36.

Future research should focus on longitudinal studies that can track long-term outcomes for children exposed to ENDS in utero, as the current body of research primarily focuses on immediate perinatal outcomes. Additionally, studies exploring the psychological and socio-economic factors influencing ENDS use during pregnancy could provide deeper insights into effective intervention strategies. Enhanced surveillance and reporting mechanisms are also crucial to monitor the impact of regulatory changes on ENDS use among pregnant women37.

Limitations

The limitations of this meta-analysis on the use of ENDS during pregnancy could include several key points. First, one of the primary limitations is the small number of studies included in this review. With only six studies meeting the inclusion criteria, the statistical power of our meta-analysis is limited. This small sample size precludes the possibility of conducting detailed subgroup or sensitivity analyses, which could provide more nuanced insights into the effects of ENDS use on specific subpopulations of pregnant women or under varying conditions. Subgroup analyses, for example, could have explored differences in outcomes based on the frequency and duration of ENDS use, the type of ENDS products used, or the presence of co-exposure to conventional cigarettes. Sensitivity analyses could have assessed the robustness of our findings to various assumptions and potential sources of bias. Second, even with a fixed-effects model used due to low heterogeneity in outcomes, differences in study design, population characteristics, definitions of exposure and outcomes, and methods of data collection across the included studies could lead to variability in results that is not fully accounted for. Third, for smoking and ENDS use, many studies rely on self-reported data, which can introduce recall bias and misclassification of exposure status. This is particularly problematic in assessing behaviors like smoking, where social desirability might influence how participants report their smoking status. Fourth, studies may not include long-term follow-up of offspring, missing potential delayed effects of ENDS use during pregnancy on children’s health beyond the neonatal period. Fifth, although some studies adjust for potential confounders like socioeconomic status, maternal age, and co-existing medical conditions, residual confounding may still exist. Some studies might not adequately control for all relevant confounders, such as paternal smoking, environmental tobacco smoke, or other substance use. Sixth, the studies included may predominantly represent specific geographical areas or cultures, limiting the findings’ generalizability to all populations. Finally, due to the rapid evolution and variation in the types of ENDS products and their use (e.g. different devices, nicotine concentrations, and flavors), findings from earlier studies may become rapidly outdated and less applicable to newer types of products.

CONCLUSIONS

This systematic review and meta-analysis highlight the significant risks associated with the use of ENDS during pregnancy. The findings confirm a link between ENDS and increased risks of adverse perinatal outcomes, including SGA infants, PB, and LBW. Despite perceptions of ENDS as a safer alternative to CCs, the evidence suggests substantial risks to fetal health from both smoking modalities. The best perinatal outcomes are consistently associated with non-smokers, indicating that complete abstinence from both CCs and ENDS is advisable for pregnant women. This review underscores the need for continued research and clear, evidence-based public health guidelines to minimize prenatal nicotine exposure from all sources.