INTRODUCTION

In 2022, tuberculosis (TB) infected 10.6 million persons worldwide and killed 1.3 million1. Indonesia has projected over 1 million TB cases and more than 0.7 million notifications. Airborne droplets from TB patients propagate Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Most TB cases in Indonesia are pulmonary (92%), with only 8% being extrapulmonary. Ocular TB is extrapulmonary TB that affects the eye and can occur with or without pulmonary TB2-4. Even in TB-endemic areas, ocular TB is rare. Several Asian countries have 0.4–9.8% ocular TB, and ocular TB in pulmonary TB is 1.4–1.8%. However, data on ocular TB varies widely due to unspecific diagnostic criteria3,5.

Ocular TB is characterized by location. Intraocular TB affects the anterior chamber, iris, corpus ciliary, vitreous, and choroid, while extraocular TB affects the orbital structures, conjunctiva, lacrimal gland, sclera, and cornea5,6. Tuberculous eye infection can have many symptoms, frequently like other ophthalmic disorders. Thus, these people are often misdiagnosed. The shortage of test specimens, lack of laboratory studies, low yield of intraocular specimens, and inconsistent diagnostic criteria make eye tuberculosis diagnosis difficult7. It makes ocular TB challenging to establish and leads to permanent disability and decreased quality of life for patients8,9. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment can prevent morbidity and blindness10. We report a case of an 18-year-old man with concurrent ocular and pulmonary TB in order to emphasize the significance of prompt recognition of the disease.

CASE PRESENTATION

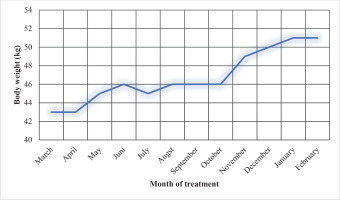

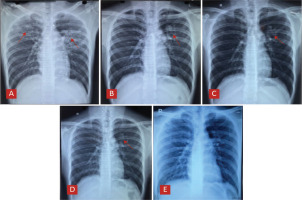

After his right eye vision gradually declined, an 18-year-old smoker visited the eye polyclinic. He reported six months of non-secretive irritated eyes and worsening vision during the preceding month. A developing white spot in the right central eye region and right eye pain and blockage were also described. The patient had received topical antibiotics, topical steroids, and symptomatic medicines, but his symptoms continued. He also had a productive cough, brownish sputum, and weight loss in the last three months, but no improvement after the treatment. Due to significant right-eye vision loss, the patient was referred to our hospital. Conjunctival flap surgery was advised as a treatment option. A diagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis was identified on the thoracic X-ray performed before the surgery procedure (Figure 1A). The pulmonologist was subsequently consulted regarding further treatment for the patient. No family medical history was found. The patient had smoked 16 cigarettes a day for two years, and he lived with his parents and two younger sisters in a crowded, well-ventilated area. Upon physical examination, the patient was underweight, with a body mass index (BMI) of 16.7 kg/m2. Right eye visual acuity was 0.25/60, with a cloudy cornea and a ±3 mm leukoma in the middle (Figure 2A). The thoracic examination revealed bronchovesicular breath sounds and rhonchi in the upper left and right lungs and the center of the left lung. The blood examinations were normal. The sputum’s smear and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests found no acid-fast bacteria or M. tuberculosis. The patient refused bronchoscopy and gastric lavage examination for sample follow-up. Due to resource constraints at our facility, we cannot conduct the M. tuberculosis culture. Pathology on sclera scraping samples showed caseous necrosis, a sign of tuberculous inflammation (Figures 2B and 2C). The patient was then diagnosed with extraocular TB, coexisting pulmonary tuberculosis, and malnutrition. The fixed medication combination of rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), pyrazinamide (Z), and ethambutol (E) was given for two months and continued with R and H for ten months. He also received topical steroids and cycloplegics. A corneal descemetocele was found during therapy, reducing right eye visual acuity to 1/300. In the fifth month of treatment, the patient had an optical iridectomy to improve vision (Figure 2D). Following a 12-month course of antituberculosis therapy, the patient’s coughing and production of phlegm resolved, and there was an improvement in his chest X-ray (Figures 1B–1E). The right eye’s visus advanced from 1/300 to 1/60. The patient’s weight increased by 8 kg (Figure 3). Mild joint pain and hyperuricemia side effects were managed with oral acetaminophen and allopurinol. Unfortunately, right eye vision was impaired by fibrosis tissue after the corneal injury healed (Figure 2E).

Figure 1

Chest X-ray series of the patient: A) Chest X-ray before treatment of antituberculosis drugs, fibroinfiltrates bilateral; B) After two months of treatment, fibroinfiltrate decreased; C) After six months of treatment, there is reduce of fibroinfiltrate lesion; D) After nine months of treatment with minimal fibroinfiltrate lesion; and E) After 12 months of treatment, normal chest X-ray

DISCUSSION

Ocular TB is one of the rare extrapulmonary TB infections, even in TB-endemic areas like Indonesia. Ocular TB prevalence data are still inconsistent due to nomenclature, diagnostic criteria, and management7. Ocular TB can be induced by direct infection from an external source (primary), hematogenous dissemination of M. tuberculosis from pulmonary or extrapulmonary foci (secondary), or ocular hypersensitivity reactions to TB antigens8,9. Besides the eye symptoms, classic pulmonary TB symptoms such as chronic cough, decreased appetite, weight loss, and night sweats can also occur in ocular TB infection with coexisting pulmonary TB. To diagnose ocular TB, tissue or ocular fluid samples are required for BTA smear, culture, or PCR analysis. Culture is the definitive test for extraocular TB. However, the sampling procedure is complex and has a high risk of causing permanent vision loss due to cataracts, retinal detachment, or infection. Due to low sensitivity, results are not always adequate. Other supportive tests like the Mantoux test and interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) can confirm the diagnosis but cannot distinguish between active or latent infection. However, they can support the diagnosis of intra- and extra-ocular TB, especially when additional evidence is lacking. Chest X-ray examination can also be performed to look for TB lesions in the lung, the most common TB-infected organ. When definitive diagnostic measures are not possible, but there are clinical manifestations of ocular TB or an inflammatory process in the eye that do not respond to standard therapy, accompanied by TB exposure (positive results on immune response tests such as Mantoux and IGRA), or evidence of a cured TB process or active TB infection on radiologic examination, it can be assumed that ocular TB has been established and treatment is required11. In this case, the patient has felt a gradual decrease in vision for six months ago and a whitish spot for three months, along with pain and blocking in the right eye. It was diagnosed as a corneal ulcer but did not respond to standard therapy. Pathology of sclera scraping revealed caseous necrosis indicative of tuberculosis inflammation. Chronic productive cough symptoms and weight loss were also reported, and an active pulmonary TB lesion was found on the chest X-ray.

Ocular TB is treated with antituberculosis medications like other extrapulmonary TB. Several reports have shown that treatment for ocular tuberculosis can be given for 6–15 months and that prolongation of antituberculosis therapy can reduce the recurrence rate. Topical medications such as steroids and cycloplegics can also be given8,11,12. In this case, the treatment used RHZE for two months, followed by ten months of RH, topical steroids, and cycloplegic. The total duration of 12 months of treatment is chosen based on the patient’s clinical condition and to prevent the recurrence of the infection. The use of ethambutol is known to cause side effects such as optic neuropathy, but it is one of the first-choice drugs to treat ocular TB. Therefore, the use of ethambutol also requires supervision by an ophthalmologist at least every two months13, as in this patient. Even with appropriate management, corneal ulcers can cause leukoma, corneal perforation, glaucoma, cataracts, and reduced vision14. From the physical examination, leukoma measured ± 3 mm in the center of the cornea with a vision of 0.25/60 and deteriorating to 1/300. The patient received an optical iridectomy to create an artificial pupil because the corneal ulcer in his right eye had developed into a leukoma and formed a cicatrix in the center, blocking light from entering the pupil. Although the vision cannot become perfectly normal, the treatment improved vision from 1/300 to 1/60, stopping inflammation and preventing corneal perforation. Antituberculosis therapy in ocular TB is associated with a good prognosis, but the severity of the lesions also influences treatment outcomes. The occurring lesions can develop into fibrous tissue if there is persistent epithelial damage3. A corneal transplant can restore the patient’s vision. However, this procedure could not be performed at our hospital because of limited resources.

CONCLUSION

This case report describes a young male active smoker with extraocular TB coexisting pulmonary TB. The diagnosis was supported by histopathology from sclera scrapping and chest X-ray. The patient had antituberculosis medicines, topical steroids, cycloplegics, and optical iridectomy to improve right oculi vision. Sadly, the fibrosis tissue formed after the corneal damage healed and caused reduced vision in the right eye.