INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) has an abundance of clinical manifestations from the immediate viral infection complications to long-term consequences after recovery1-3. Notably, the virus frequently affects the nervous system4, with sleep disturbances as a prevalent neurological symptom, especially in the initial stages of the infection4.

The pervasive impact of COVID-19 on sleep is multifaceted, as it involves physiological changes, psychological stress, and chronic health alterations induced by the virus5. In this context, researchers have tried to determine if there is an association between the sleep disorders and the subsequent effects of COVID-19 including the psychological and mental disorders associated with COVID-19, such as anxiety, depression, stress and decreased life satisfaction6-8. Extensive research has underscored the broad impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental and physical health. The pandemic itself, along with the prolonged quarantine measures, significantly affected the individuals’ sleep patterns, with symptoms of chronic fatigue and mood disorders across various demographics, including caregivers, healthcare workers, and the general population9. Systematic meta-analyses using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) have revealed that sleep disturbances are alarmingly prevalent, affecting 57% of COVID-19 patients and up to 74.8% of the general population, with older males showing particularly high rates of sleep issues9,10. These findings suggest a complex, bi-directional relationship between SARS-CoV-2 infection and sleep quality. Additionally, the fear of COVID-19 has been linked with worse quality of sleep, with increased anxiety and negative impact on life satisfaction, and well-being11. This association between poor sleep and diminished quality of life highlights the significant socio-emotional and health-related consequences of the pandemic.

The primary objective of this study is to elucidate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological well-being of affected patients, with an emphasis on its influence on sleep and overall mental health. This study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the interrelationships between the pandemic’s stressors and their consequent effects on individual psychological states. By investigating these dynamics, this research seeks to contribute valuable insights into the broader implications of COVID-19 on public health and inform potential strategies for mitigating its adverse effects on mental health.

METHODS

Study design

The survey was conducted from 24 October 2022 to 24 January 2023. The aim of this study was to record the general population’s experiences associated with COVID-19 recovery, with emphasis on mental health and sleep disturbances. The data were collected via questionnaires from 300 patients with a history of COVID-19 infection, who had been hospitalized in the General Hospital of Drama or had received home care, 12 months after the infection. We thoroughly informed all potential subjects about the study’s objectives and obtained their voluntary consent prior to enrollment. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the General Hospital of Drama (455/21-10-2022), and participants received the questionnaires on paper along with an informed-consent form. The study was conducted in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection instruments and procedures

A structured questionnaire was used to collect the data, divided into several sections (Supplementary file).

Demographics and clinical profile

The first section captured demographic details such as gender, age, marital status, place of residence, and education level. It also included specific questions related to the participants’ COVID-19 infection history, such as date of diagnosis, duration of hospitalization, intensive care unit admissions, vaccination status, ongoing medications, and comorbid conditions.

Sleep assessment using the Athens Insomnia Scale

The second section incorporated the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), validated for the Greek population12. This self-assessment tool, based on ICD-10 criteria, consists of eight questions addressing various aspects of sleep quality and disturbances. We scored the responses on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘good sleep’) to 3 (‘symptoms of insomnia’), with a composite score of 6 or higher indicating insomnia.

Fatigue Severity Scale

The third section used the Fatigue Severity Scale13, validated for the Greek population14. It includes nine items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, where a cumulative score above 36 indicates significant fatigue and functional impairment.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

The fourth section utilized the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)15, which assesses various dimensions of sleep quality over the preceding past 30 days. A Greek version of the questionnaire was used to determine overall sleep quality16.

Generalized anxiety and depression assessment

Subsequent sections included the General Anxiety Disorder -7 (GAD-7) scale for anxiety17 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression18. Both scales utilize a 4-point Likert response format to gauge the severity of symptoms over the past two weeks.

Impact of Event Scale, COVID-19 version

The final section incorporated the modified Impact of Event Scale (IES) for COVID-19, which assesses the psychological responses to the pandemic over the previous week on a scale from 0 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘often’)19.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize both continuous and categorical variables, such as frequencies, means with standard deviation (SD), and medians with interquartile range (IQR). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed distribution normality. We applied non-parametric tests such as the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests for comparative analyses. Spearman’s rho was used to determine the association between continuous variables, and linear and logistic regression analyses were performed to examine factors that could predict different psychological and sleep-related outcomes. We set the statistical significance at a two-sided p<0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

A total of 300 participants (146 men and 154 women) were enrolled in the study. The average age of this cohort was 51.8 ± 14.6 years, and the majority of the participants (71.3%) reported being married. Only 21.3% had no children and 19.3% were living alone, highlighting diverse living conditions within the sample. Participants’ education level varied, with 32.7% reporting high school completion. The majority of participants (71%) resided in urban areas, reflecting a predominantly city-based demographic. Additionally, 33.7% of the respondents were employed as civil servants. Demographic characteristics are summarized in more detail in Supplementary file Table 1.

Medical history and COVID-19-related experiences

COVID-19 infection occurred at least 12 months before the study was conducted, with 52% of the participants requiring hospitalization, with a mean hospital stay of 7.3 ± 10 days. Intensive care unit (ICU) admission was reported by 8 individuals (2.7%). At the time of the study, 34.3% of the participants were fully vaccinated for COVID-19.

Comorbid conditions were prevalent among the participants, with two-thirds (66.7%) reporting at least one accompanying chronic disease. Hyperlipidemia and arterial hypertension were the most prevalent, affecting 48.7% and 46.7% of the participants, respectively. Medical history and COVID-19-related experiences are summarized in Supplementary file Table 2.

Association of IES-COVID-19 with demographicclinical characteristics

The median value in the dimension ‘Intrusion’ and ‘Avoidance’ was 6 points (IQR: 5–16) and 8 points (IQR: 2–18), respectively, and the median total score of IES-COVID-19 was 15 units (IQR: 4–36).

The gender, the residency, and the hospitalization status emerged as significant independent variables for the IES-COVID-19 scores. Analysis revealed a pronounced disparity in IES-COVID-19 scores between genders, with the females reporting higher scores compared to males (p=0.005). Furthermore, participants residing in small towns exhibited elevated scores (p=0.037). Notably, the highest IES-COVID-19 scores were observed in participants who required hospitalization (p<0.001). The association of IES-COVID-19 scores with demographic-clinical characteristics is summarized in Table 3 (Supplementary file Table 3).

Association of sleep quality (AIS, PSQI) with demographic-clinical characteristics and IES-COVID-19

In regard to the rate of insomnia (assessed with the AIS scale) and the quality of sleep (assessed with the PSQI scale), it was found that 158 (52.7%) participants suffered from insomnia, and 139 (46.3%) participants had poor sleep quality.

The analysis identified several independent associations between participants’ experiences with COVID-19 and their insomnia symptoms. Hospitalization during the COVID-19 illness significantly influenced sleep disturbances, with participants experiencing a 2.11-fold higher likelihood of insomnia compared to those not hospitalized (p=0.012). Additionally, attitudes toward vaccination also impacted insomnia rates. Participants who were either undecided or did not wish to receive the COVID-19 vaccine reported a 48% lower probability of suffering from insomnia compared to those who had received or intended to receive the vaccine (p=0.05). Furthermore, a correlation between the psychological impact of COVID-19 on participants and the prevalence of insomnia was observed (p<0.001) (Supplementary file Table 4).

The analysis also identified a significant independent relationship between IES-COVID-19 scores and participants’ sleep quality as estimated by PSQI. Specifically, it was demonstrated that an increased psychological impact of the disease significantly correlated with poorer sleep quality. Participants experiencing higher levels of psychological distress due to COVID-19 were more likely to report diminished sleep quality (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for PSQI

Association of GAD-7 and PHQ-9 with demographic-clinical characteristics, IES-COVID-19 and sleep quality (AIS, PSQI)

The median GAD-7 score was 6 points (IQR: 1–11). It was found that 43.7% of the participants had no symptoms of anxiety, 24.3% experience anxiety for several days, 19.7% experienced anxiety more than half the days, while 12.3% experienced anxiety nearly every day.

The PHQ-9 score of the participants was 6.6 ± 6.4 points. Based on the results, depression ranged as follows: 26.8% had moderate to severe depression, 24.7% had mild depression. 48.5% showed no symptoms of depression, while 7.4% showed symptoms of severe depression.

Several factors were independently associated with the anxiety scores among participants. Specifically, hospitalization due to COVID-19 significantly increased anxiety symptoms, with hospitalized participants reporting higher levels of anxiety compared to those not hospitalized (p=0.05). Furthermore, participants experiencing greater psychological distress from COVID-19 exhibited more severe anxiety symptoms, a direct correlation between the psychological impact of the pandemic and increased anxiety (p<0.001). Additionally, we observed a strong relationship between insomnia and anxiety, with more anxiety symptoms among participants experiencing insomnia (p<0.001). Conversely, increased anxiety was associated with poorer sleep quality (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2

Multivariate linear regression analysis for GAD-7

| Variable | b+ | SE++ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male ® | |||

| Female | 0.016 | 0.039 | 0.684 | |

| Age (years) | -0.001 | 0.002 | 0.536 | |

| Live with a partner | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.025 | 0.076 | 0.746 | |

| Have children | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.094 | 0.062 | 0.129 | |

| Live alone | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.048 | 0.084 | 0.565 | |

| Education level | Primary school ® | |||

| Secondary school | 0.091 | 0.062 | 0.144 | |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s /Doctorate | -0.020 | 0.069 | 0.77 | |

| Place of residence | City ® | |||

| Town | 0.001 | 0.059 | 0.99 | |

| Village | 0.020 | 0.053 | 0.713 | |

| Hospitalized patient | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.081 | 0.042 | 0.050 | |

| Hospitalized in an ICU | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.029 | 0.121 | 0.813 | |

| Willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 | I want to be/have been vaccinated ® | |||

| I don’t want to be vaccinated/I haven’t decided | -0.073 | 0.047 | 0.119 | |

| Comorbidities | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.020 | 0.049 | 0.685 | |

| IES-COVID-19 | 0.009 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Insomnia | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.200 | 0.049 | <0.001 | |

| Sleep quality | Good ® | |||

| Poor | 0.185 | 0.051 | <0.001 |

The analysis indicated that IES-COVID-19 score, insomnia symptoms, and sleep quality were independently associated with the PHQ-9 scores among participants. Notably, an increase in the psychological impact of COVID-19 on participants was associated with heightened symptoms of depression (p<0.001). Additionally, it was observed that participants experiencing insomnia exhibited more severe symptoms of depression (p<0.001), which in turn adversely affected their sleep quality (p=0.025) (Table 3).

Table 3

Multivariate linear regression analysis for PHQ-9

| Variable | b+ | SE++ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male ® | |||

| Female | 0.050 | 0.037 | 0.170 | |

| Age (years) | -0.002 | 0.002 | 0.185 | |

| Live with a partner | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.063 | 0.072 | 0.379 | |

| Have children | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.102 | 0.058 | 0.077 | |

| Live alone | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.077 | 0.078 | 0.328 | |

| Education level | Primary school ® | |||

| High school | 0.003 | 0.058 | 0.961 | |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s /Doctorate | -0.066 | 0.065 | 0.309 | |

| Place of residence | City ® | |||

| Town | 0.033 | 0.056 | 0.552 | |

| Village | 0.082 | 0.050 | 0.104 | |

| Hospitalized patient | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.014 | 0.039 | 0.724 | |

| Hospitalized in an ICU | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.077 | 0.113 | 0.494 | |

| Willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 | I want to be/have been vaccinated ® | |||

| I don’t want to be vaccinated/I haven’t decided | -0.052 | 0.044 | 0.239 | |

| Comorbidities | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.037 | 0.046 | 0.419 | |

| IES-COVID-19 score | 0.008 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Insomnia | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.297 | 0.046 | <0.001 | |

| Sleep quality | Good ® | |||

| Poor | 0.106 | 0.047 | 0.025 | |

Association of FSS with all elements of the study

The median FSS score was 29 (IQR: 18–43). A significantly higher score therefore was observed by the participants who needed to be hospitalized (p<0.001). Table 4 shows participants’ FSS scores according to their demographic characteristics and medical history.

Table 4

FSS scores based on demographic and clinical characteristics

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 30.1 (16.1) | 27.5 (16–43) | 0.397+ |

| Female | 31.4 (15.3) | 30 (19–43) | ||

| Live with a partner | No | 30.3 (15.5) | 28.5 (18–43) | 0.744+ |

| Yes | 30.9 (15.8) | 29 (18–43) | ||

| Have children | No | 28.4 (14.3) | 26 (15.5–38.5) | 0.206+ |

| Yes | 31.4 (16) | 30 (18–45) | ||

| Live alone | No | 30.8 (15.6) | 29 (18–43) | 0.823+ |

| Yes | 30.6 (16.2) | 26 (18–44) | ||

| Education level | Primary school | 32.3 (15.5) | 27 (20–47) | 0.112++ |

| Secondary school | 32.7 (16.7) | 31 (18–49) | ||

| Bachelor’s/Master’s /Doctorate | 28.5 (14.6) | 27 (16–40) | ||

| Place of residence | City | 29.6 (14.8) | 28 (18–40) | 0.178++ |

| Town | 32.3 (18.5) | 29 (15–50) | ||

| Village | 34.5 (16.6) | 36 (19–50) | ||

| Hospitalized patient | No | 23.7 (12.3) | 22 (14–31) | <0.001+ |

| Yes | 37.3 (15.6) | 39 (23–51) | ||

| Hospitalized in an ICU | No | 30.5 (15.6) | 28.5 (18–43) | 0.128+ |

| Yes | 39.5 (18.2) | 41.5 (21.5–56.5) | ||

| Willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 | I want to be/have been vaccinated | 31.5 (16.1) | 29 (18–45) | 0.198+ |

| I don’t want to be vaccinated/I haven’t decided | 28.2 (13.9) | 26 (18–37) | ||

| Comorbidities | No | 28.3 (12.9) | 28.5 (18–36) | 0.139+ |

| Yes | 32 (16.8) | 29 (18–47) | ||

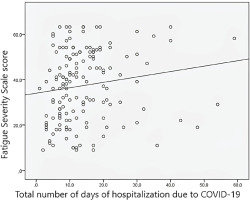

In hospitalized patients, a statistically significant correlation between the total days of hospitalization for COVID-19 disease and FSS score was observed (Spearman’s rho=0.210, p=0.007) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Correlation of Fatigue Severity Scale score with total number of days of hospitalization due to COVID-19

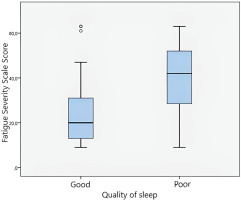

The median FSS score was 42 (IQR: 28–52) in patients with poor sleep quality and 20 (IQR: 13–31) in patients with good sleep quality (p<0.001). The median FSS score was 40.5 (IQR: 26–52) in patients with insomnia and 20 (IQR: 12–31) in those without insomnia (p<0.001).

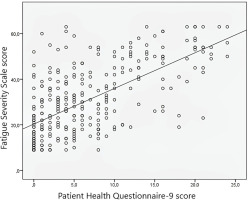

A statistically significant correlation was found between the FSS score of the participants with PHQ-9 score (Figure 2), GAD-7 score, and IES-COVID-19 score (r=0.630, p<0.001; r=0.530, p<0.001; and r=0.510, p<0.001, respectively).

The analysis also revealed that hospitalization, sleep quality, and PHQ-9 scores were independently associated with FSS scores among participants. Specifically, those who required hospitalization reported higher levels of fatigue (p<0.001). Furthermore, participants experiencing insomnia or poor sleep quality also reported increased fatigue (p=0.001 and p=0.045, respectively). Additionally, a correlation between the severity of depression symptoms and fatigue was observed, indicating that participants with more intense depression symptoms also experienced greater fatigue (rho=0.63, p<0.001) (Figure 3). These findings underscore the multifaceted impact of health status, sleep disturbances, and mental health on fatigue levels (Table 5).

Table 5

Multivariate linear regression analysis for FSS

| Variable | b+ | SE++ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male ® | |||

| Female | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.156 | |

| Age (years) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.796 | |

| Live with a partner | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.039 | 0.044 | 0.379 | |

| Have children | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.019 | 0.036 | 0.593 | |

| Live alone | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.063 | 0.048 | 0.195 | |

| Education level | Primary school ® | |||

| High school | -0.022 | 0.036 | 0.545 | |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s /Doctorate | -0.049 | 0.04 | 0.216 | |

| Place of residence | City ® | |||

| Town | -0.059 | 0.034 | 0.090 | |

| Village | -0.020 | 0.031 | 0.520 | |

| Hospitalized patient | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.128 | 0.024 | <0.001 | |

| Hospitalized in an ICU | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.002 | 0.07 | 0.982 | |

| Willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19 | I want to be/have been vaccinated ® | |||

| I don’t want to be vaccinated/I haven’t decided | 0.021 | 0.027 | 0.430 | |

| Comorbidities | No ® | |||

| Yes | -0.018 | 0.028 | 0.525 | |

| Sleep quality | Good ® | |||

| Poor | 0.098 | 0.03 | 0.001 | |

| Insomnia | No ® | |||

| Yes | 0.075 | 0.03 | 0.045 | |

| PHQ-9 | 0.012 | 0.003 | <0.001 | |

| CAD-7 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.724 | |

| IES-COVID-19 score | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.361 | |

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study align with those of previous studies20,21, highlighting the COVID-19 pandemic as a significant source of stress, which leads to increased sleep disturbances and a deterioration in sleep quality22,23. Furthermore, the mental strain from contracting COVID-19 impacted various sleep-related issues among participants, such as difficulty initiating and maintaining sleep and disrupted sleep patterns, particularly during quarantine periods, as observed by Casagrande et al.24.

Additionally, participants hospitalized due to COVID-19 exhibited a higher likelihood of insomnia, being about 2 times more susceptible compared to non-hospitalized individuals. This finding is consistent with the study of Van den Ende et al.25 who found a five-fold increase in insomnia risk among hospitalized patients. However, it remains unclear whether these sleep disturbances are directly due to hospitalization26 or a result of symptoms such as anxiety or dyspnea27 or the virus invasion of the CNS28.

An intriguing finding of this study was that participants who were hesitant or undecided about the COVID-19 vaccination were 48% less likely to suffer from insomnia compared to those intending to get vaccinated. As mentioned previously, the fear of COVID-19 is linked to worse quality of sleep, increased anxiety and negative impacts on life satisfaction and well-being11. Thus, those individuals having no, or minimal fear of getting infected (a fact that probably led them to avoid vaccination) had better sleep quality.

The study noted moderate anxiety levels among participants, with nearly half exhibiting no depressive symptoms. However, hospitalized individuals showed heightened anxiety, which augmented further in those severely impacted by COVID-19. Increased anxiety levels correlated with worsened sleep quality among those suffering from insomnia, in agreement with Wang et al.29. Similarly, previous studies22,30, identified high stress levels as detrimental to sleep quality.

Furthermore, the study confirmed that a greater psychological impact from COVID-19 enhanced depressive symptoms, particularly among patients with insomnia, resulting in poorer sleep quality. This aligns with findings by Zhai et al.31 that linked poor sleep quality to psychological disorders like depression. Supporting this, research by Grasso et al.32 indicated that adverse changes during quarantine, such as sleep difficulties, were associated with increased depression and anxiety rates.

Participants exposed to Covid- 19 infection reported a higher fatigue rate, which increased with the length of hospitalization. This association between insomnia, poor sleep quality, and fatigue aligns with observations by Mello et al.33 and Liu et al.34 who noted complaints of insomnia, fatigue, and depressive symptoms among COVID-19 patients. A positive correlation was also noted between physiological impacts from COVID-19 and an increase in depressive symptoms, anxiety, and fatigue, consistent with findings by other researchers9.

Limitations

The study encountered several challenges, particularly due to the enrolment period during the pandemic. The chosen research tool and its length, which required substantial time to complete, were significant limitations and compelled some of the participants to refuse or withdraw from the study. Additionally, the paper-based format of the questionnaire was difficult to read by older participants or those with visual impairments, potentially skewing the sample towards those that were more comfortable with written forms.

The distribution of questionnaires was confined to the hospital setting, limiting the ability to generalize the results to the general population. Also, this methodological choice limits the results’ applicability to other contexts and demographic groups beyond the hospital’s geographical area.

Moreover, the relatively short data collection period poses a limitation. While the number of responses obtained was satisfactory, the short timeframe may have precluded the accumulation of a larger and more diverse sample, which could have provided more representative and robust findings. This factor is crucial in understanding the scope and applicability of the study’s conclusions, particularly in such a dynamic and globally impactful context as the COVID-19 pandemic.

CONCLUSIONS

This study illustrates that COVID-19 significantly impacts psychological health, sleep disorders, and broader mental health outcomes, particularly in patients needed hospital admission. The last was associated with higher psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and fatigue, along with deteriorated sleep quality. Additionally, prevalent sleep disturbances like insomnia and poor sleep quality not only stemmed from the virus but also intensified mental health issues, thereby contributing to overall health decline. The strong correlation between psychological distress and adverse health outcomes indicates the need for targeted mental health interventions and continuing research in order to fully understand and mitigate the long-term effects on public health of COVID-19.