Congenital bronchial atresia is a rare abnormality of the tracheobronchial tree. In clinical practice, 60% of patients can be either asymptomatic or may have symptoms like recurrent pneumonias, dyspnea, cough or hemoptysis.

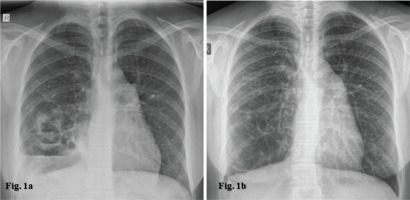

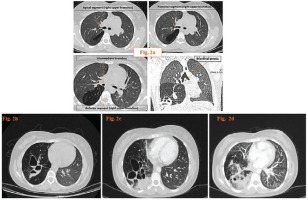

A 27-year-old-female was admitted to our hospital with a fever and right-sided chest pain. The patient was a non-smoker without any chronic disease from her medical history. She only mentioned past hospitalizations for pneumonia in early childhood, but she does not adduce any previous chest imaging. Physical examination was unremarkable except for diminished breath sounds over the lower right hemithorax. Laboratory results showed leukocytosis with a white blood cell (WBC) count of 16.7×103/mL and a marked elevated C-reactive protein (27.15 mg/dL). The chest-x-ray revealed cavitary lesions with air-fluid levels at the right lower lung field (Figure 1 a). Chest computed tomography (CT) scan findings included bronchial dilation and multiple cavitary lesions in the right middle and lower lobe with air-fluid levels, and focal obliteration of the intermediate bronchus (Figure 2 a). Moreover, there was hyperinflation of the surrounding lung parenchyma, accompanied by vascular desertification (Figures 2 b, c, and d).

Figure 1

a) The admission chest x-ray showing cavitary lesions with air-fluid levels at the right lower lung field; b) The follow-up chest x-ray with remission of air-fluid levels

Figure 2

a) Axial computed tomography (CT) images showing the proximal bronchial anatomy and coronal reconstruction image depicting the bronchial atresia; and Thorax contrast-enhanced CT: b and c) bronchial dilation and multiple cavitary lesions in the right middle and lower lobe with air-fluid levels, compatible with mucoceles; d) hyperinflation of the surrounding lung parenchyma and vascular desertification

She was treated with antibiotics for 14 days with a provisional diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia complicated by lung abscess formation. Subsequently, she was subjected to bronchoscopy, which after the main carina revealed three segmental bronchi for the right upper lobe (Figure 3 a) and a blind-ending orifice which probably corresponds to the atretic segments for the right middle and lower lobe (Figures 3 b and c). Two weeks after the initial evaluation the patient was discharged in good medical condition. On her follow-up three weeks later, she was asymptomatic and chest x-ray revealed remission of air-fluid levels (Figure 1 b).

Figure 3

Bronchoscopic images showing: a) three segmental bronchi for the right upper lobe; b and c) a blind-ending orifice which probably corresponds to the atretic segments for the right middle and lower lobe

The correlation of CT and bronchoscopic findings established the diagnosis of congenital bronchial atresia. Bronchial atresia is a rare congenital abnormality in which the bronchus lacks central airway communication1. It is hypothesized to occur as focal bronchial interruption due to intrauterine ischemia after the 16th week of gestation2. Chest x-ray findings typically show hyperlucency, hilar mass, or both. CT is the gold standard for its diagnosis and the main findings are bronchocele, hyperinflation of the distal lung, and hypovascularity3,4. The main characteristic of bronchoceles is the mucoid impaction of atretic segment. Hyperinflation can be explained by collateral ventilation through the pores of Kohn, bronchoalveolar channels of Lambert, or via air-trapping due to check valve mechanism5. Despite these almost pathognomonic findings, it is necessary to differentiate unilateral hyperlucency from Swyer-James syndrome. It describes an acquired condition that usually develops during childhood as a sequel of post-infectious bronchitis obliterans, leading to the dilation and destruction of lung parenchyma with air trapping1 and underdevelopment of the peripheral pulmonary vessels. The CT finding of a normal distal bronchial branch pattern without a connection between the distal and central airways is essential to differentiate bronchial atresia from Swyer-James syndrome1. Other congenital situations that should be included in differential diagnosis are congenital lobar emphysema, pulmonary sequestration and congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation, as there are possible common pathogenic pathways. During adulthood, the surgical treatment is meant for patients who present repeated infections6.